Background

Propensity score matching (PSM) is among the most popular methods for estimating causal effects with observational data. It lends its fame to both its power and simplicity. Under a certain set of commonly invoked assumptions, controlling for the propensity score alone (as opposed to the full set of covariates) is enough to remove bias between the treatment and control groups. The underlying idea of matching on the propensity score is incredibly simple and most data scientists can quickly estimate a treatment effect even from scratch.

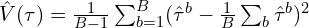

While estimating treatment effects is common and straightforward, calculating their variance along with the associated confidence intervals and ![]() -values can be more challenging. So, how exactly do you compute the variance of PSM methods? In this article I will describe the most popular ways of doing that. My goal is to cover the intuition and I will spare the technical details. Interested readers can refer to the References section below for more detailed expositions.

-values can be more challenging. So, how exactly do you compute the variance of PSM methods? In this article I will describe the most popular ways of doing that. My goal is to cover the intuition and I will spare the technical details. Interested readers can refer to the References section below for more detailed expositions.

Statistical methods based on the propensity score function come in different flavors (e.g., weighting, matching, subclassification, etc.), but today I will focus on 1:1 or 1:N matching. There are also several potential estimands of interest, such as ATE (average treatment effect), ATT (ATE for the treatment group) but I will talk specifically about the latter.

In brief, the idea behind treatment effect estimation with PSM is:

- Estimate the propensity score (i.e., the probability of being in the treatment group).

- For each user in the treatment group find the user(s) in the control group with the most similar predicted propensity score value.

- Analyze the outcome differences in each pair to arrive at a final ATT (or ATE) estimate.

Throughout the article, I will assume a standard, well-behaved setting with SUTVA, unconfoundedness, and overlap assumptions in place. Similarly, I will ignore many important aspects of PSM methods such as trimming, propensity score and even treatment effect estimation. I will also use standard notation (e.g., ![]() and

and ![]() denote outcome and treatment; and

denote outcome and treatment; and ![]() is the ATT) without setting up the entire framework.

is the ATT) without setting up the entire framework.

Types of Methods

We can classify the methods for estimating the PSM variance in three distinct buckets.

Asymptotic Approximation

Recall the Law of Total Variance stating that, given a conditioning variable ![]() , we can always decompose a random variable

, we can always decompose a random variable ![]() ’s variance, into two components – the expectation of the conditional variance and the variance of the conditional expectation:

’s variance, into two components – the expectation of the conditional variance and the variance of the conditional expectation:

(1) ![]()

Abadie and Imbens (2006) use this idea to derive the asymptotic variance formula for one-to-one and one-to-many matching estimators. They provide an analytical expression for the variance as ![]() (and hence, this is an approximation) using the matching covariates as conditioning variables. I will not be going into their work in detail, but a couple of notes are worth discussing.

(and hence, this is an approximation) using the matching covariates as conditioning variables. I will not be going into their work in detail, but a couple of notes are worth discussing.

The original formulation assumes the true propensity score function is known. This is rarely true and in practice we rely on an estimate of it. Practitioners then replace this true propensity score with the estimated one. This is OK, but not great – it brings me to the second issue.

One needs to account for the fact that this propensity score is estimated. As such, it comes with uncertainty, which, if ignored, can potentially understate the variance of your estimator. Hello, type 1 errors!

In follow-up work, Abadie and Imbens (2016) propose correction which accounts for this uncertainty. Interestingly, in a work that I will discuss below, Bodory et al. (2020) report that in practice this correction might increase or decrease the ATT variance.

Approximation Based on Weights

We can express all treatment effect estimators as a difference of weighted means:

![]()

where the weights ![]() may depend on the propensity score.

may depend on the propensity score.

Lechner (2002) suggested calculating the variance of PSM based on this formula, assuming the weights are non-stochastic. In other words, the approach ignores the fact that the propensity score is estimated in a first step. The PSM variance is then equal to the sum of two terms – the one for the treated and the one for the control.

Bootstrap

Bootstrap is the go-to method for estimating variances in complex settings where analytical expressions are too messy or even do not exist. PSM seems like a natural environment where the bootstrap can help. Not so fast!

Abadie and Imbens (2006) show that the standard nonparametric bootstrap is inconsistent for non-smooth estimators (such as propensity score matching) with fixed number of matches and continuous covariates. Nevertheless, practitioners routinely ignore this result. While the theory says we should not use the bootstrap here, the extent to which this is of practical relevance is unclear. For instance, if this only makes a difference in the fourth decimal, we might be willing to sacrifice some bias for ease of computation.

There are at least two ways one can go around using the bootstrap here. The first one is the standard plain vanilla approach.

- Randomly draw

samples of size

samples of size  .

.

- Alternatively, you can also sample directly from the matched pairs which works better in certain cases.

- Compute ATT each time.

- Compute the confidence interval:

where![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\hat{\tau}\pm \sqrt{\hat{V}(\hat{\tau}) \times c},\]](https://yasenov.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7b7adab9202a3b6bf8edf812735eeeb2_l3.png)

is the bootstrap variance of

is the bootstrap variance of  and

and  is the critical value associated with a confidence level

is the critical value associated with a confidence level  .

.

Alternatively, in this last step we can directly use the ![]() and 1-

and 1-![]() quantiles of the bootstrap distribution of

quantiles of the bootstrap distribution of ![]() .

.

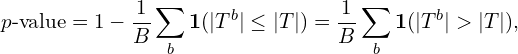

The second approach uses the well-known fact that the bootstrap behaves better when it uses so called asymptotically pivotal statistics – i.e., ones which asymptotic distribution does not depend on unknown quantities. In this setting a candidate would be the ![]() -statistic which, as we know, under certain conditions has a standard normal asymptotic distribution. We proceed in three steps:

-statistic which, as we know, under certain conditions has a standard normal asymptotic distribution. We proceed in three steps:

- Compute the

-stat in the main sample using one of the variance approximations.

-stat in the main sample using one of the variance approximations. - Draw

random samples of size

random samples of size  and we compute the recentered

and we compute the recentered  -stat with respect to

-stat with respect to  in the main sample,

in the main sample,

- The

-value is the share of (absolute value) bootstrap

-value is the share of (absolute value) bootstrap  -stats larger than the absolute value of the

-stats larger than the absolute value of the  -stat in the main sample

-stat in the main sample

where ![]() is the

is the ![]() -stat from the main sample.

-stat from the main sample.

There are also newer (wild) bootstrap ideas which are still making their way into the mainstream.

Monte Carlo Simulations

Bodory et al. (2020) compare the finite sample performance of several of these methods (plus others). Their analysis is more thorough in the sense that they include other ATT estimators besides PSM, such as PS weighting or radius matching.

Overall, their results do not indicate a clear winner which performs best in all scenarios. Interestingly, even some of the bootstrap methods often outperform the asymptotic approximations of Abadie and Imbens (2006) or Lechner (2002).

Where to Learn More

I based this post on Bodory et al. (2020)’s paper, so that is a natural place to start. Many other studies have focused on the performance of propensity score treatment effect estimators (as opposed to their variance) – Huber et al. (2013) and Busso et al. (2014) are great starting points. Lastly, Imbens (2015) is a great resource for an overview of matching methods more generally along with some of the problems they solve as well as the pitfalls they entail.

Bottom Line

- There is no shortage of methods when it comes to estimating the variance of propensity score matching estimators.

- Abadie and Imbens (2006) showed that the standard bootstrap is inconsistent in this setting with continuous covariates and formally derived an asymptotic approximation of the true variance.

- Monte Carlo simulations, however, show that bootstrap methods offer a good tradeoff between simplicity and performance.

References

Abadie, A., & Imbens, G. W. (2006). Large sample properties of matching estimators for average treatment effects. Econometrica, 74(1), 235-267.

Abadie, A., & Imbens, G. W. (2008). On the failure of the bootstrap for matching estimators. Econometrica, 76(6), 1537-1557.

Austin, P. C., & Small, D. S. (2014). The use of bootstrapping when using propensity‐score matching without replacement: a simulation study. Statistics in medicine, 33(24), 4306-4319.

Bodory, H., Camponovo, L., Huber, M., & Lechner, M. (2020). The finite sample performance of inference methods for propensity score matching and weighting estimators. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 38(1), 183-200.

Busso, M., DiNardo, J., & McCrary, J. (2014). New evidence on the finite sample properties of propensity score reweighting and matching estimators. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(5), 885-897.

Caliendo, M., & Kopeinig, S. (2008). Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. Journal of economic surveys, 22(1), 31-72.

Huber, M., Lechner, M., & Wunsch, C. (2013). The performance of estimators based on the propensity score. Journal of Econometrics, 175(1), 1-21.

Imbens, G. W. (2015). Matching methods in practice: Three examples. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 373-419.

Lechner, M. (2002). Some practical issues in the evaluation of heterogeneous labour market programmes by matching methods. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 165(1), 59-82.

Leave a Reply