Background

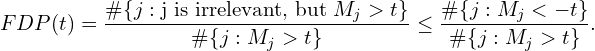

A while back I wrote an article summarizing various approaches to correcting for multiple hypothesis testing. The dominant framework, False Discovery Rate (FDR), controls the share of hypotheses that are incorrectly rejected at a pre-specified level ![]() . Its foundations were laid out in 1995 by Benjamini and Hochberg (BH) and to date, their method remains the most popular approach for controlling FDR. Since then, the literature has gone in a few directions.

. Its foundations were laid out in 1995 by Benjamini and Hochberg (BH) and to date, their method remains the most popular approach for controlling FDR. Since then, the literature has gone in a few directions.

One strand of research generalizes the BH procedure to accommodate cases in which there is a dependency (i.e., correlation) among the hypotheses being tested. Another group of papers makes use of covariates that carry information about whether a given hypothesis is likely to be false. While intuitive in theory, in practice this idea is of limited use as such covariates are not often available.

Finally, a relatively new class of methods builds on the notion of “knockoff” (or fake) variables and performs variable selection while controlling FDR. The underlying idea is based on creating a fake variable and comparing its test statistics to that of the original variable. Since the fake one is, by definition, null, a small discrepancy between the two test statistics signals the original variable does not belong in the model. The baseline model-X knockoff method requires knowledge of the joint distribution of all covariates. Recent simulations show if this distribution is unknown and misspecified (which in practice it almost always is) there is a loss of statistical power and FDR increase.

In this article I will discuss a few new papers which aim to build on and improve the knockoff method. Like knockoffs, they are based on “mirror statistics”, but unlike them they do not require exact knowledge or consistent estimation of any distribution. Specifically, I will discuss Gaussian Mirrors and Data Splitting for FDR control.

Let’s get right into it.

Notation and Setting

Although many of the results generalize to more complex settings, I will work with the simple linear model:

(1) ![]()

We have ![]() observations of an outcome

observations of an outcome ![]() , and a covariate vector

, and a covariate vector ![]() with

with ![]() . (Again, some of these results generalize to high-dimensional settings, but let’s keep it simple here.) I will index the variables in

. (Again, some of these results generalize to high-dimensional settings, but let’s keep it simple here.) I will index the variables in ![]() by

by ![]() . My goal is to find a subset of relevant features from

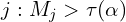

. My goal is to find a subset of relevant features from ![]() while controlling the FDR at some level

while controlling the FDR at some level ![]() . In other words, I wil be testing the series of

. In other words, I wil be testing the series of ![]() null hypotheses of the kind

null hypotheses of the kind ![]() .

.

Diving Deeper

FDR Control with Mirror Statistics

The building block of these methods are the so-called mirror statistics, ![]() . They have the following two properties:

. They have the following two properties:

- Variables with larger mirror statistics (

‘s) are more likely to be relevant.

‘s) are more likely to be relevant. - Their distribution under the null hypothesis is (asymptotically) symmetric around 0.

These properties are simple and intuitive. For instance, the commonly used ![]() -statistic for hypothesis testing in the linear model satisfies both. The first property suggests we can order the features and select ones with a mirror statistic exceeding some pre-defined threshold. The second one leads to an approximate upper bound on the number of false positives for any cutoff

-statistic for hypothesis testing in the linear model satisfies both. The first property suggests we can order the features and select ones with a mirror statistic exceeding some pre-defined threshold. The second one leads to an approximate upper bound on the number of false positives for any cutoff ![]() :

:

Now that we know the mirror statistics’ properties, I will discuss various ways of calculating them.

How to Construct the Mirror Statistics

The mirror statistics ![]() take the following general form:

take the following general form:

![]()

where the ![]() denote (standardized) estimates of the true coefficient

denote (standardized) estimates of the true coefficient ![]() and

and ![]() is a nonnegative, exchangeable and monotically increasing function. For instance, convenient choices for

is a nonnegative, exchangeable and monotically increasing function. For instance, convenient choices for ![]() include

include ![]() (Xing et al. 2019),

(Xing et al. 2019), ![]() , and

, and ![]() (Dai et al. 2022).

(Dai et al. 2022).

Let’s now turn to calculating the ![]() s.

s.

How to Construct the Regression Coefficients

The coefficients ![]() ought to satisfy the following two conditions:

ought to satisfy the following two conditions:

- Independence – The two regression coefficients are (asymptotically) independent.

- Symmetry – Under the null hypothesis, the (marginal) distribution of either of the two coefficients is (asymptotically) symmetric around zero.

I will now describe two approaches in constructing them.

Approach #1 – Gaussian Mirrors

Software Package: GM

The main idea is to create a set of two perturbed mirror features for each variable ![]() . Namely,

. Namely,

![]()

where ![]() is a scalar and

is a scalar and ![]() . The authors provide some guidance on how to select

. The authors provide some guidance on how to select ![]() , but I will not get into that here.

, but I will not get into that here.

While it is possible to generate the mirror features for all columns in ![]() simultaneously, the one-fit-per-feature approach shows better performance in simulations. So, the

simultaneously, the one-fit-per-feature approach shows better performance in simulations. So, the ![]() are the estimates of

are the estimates of ![]() in the following model:

in the following model:

![]()

Approach #2 – Data Splitting

An alternative approach for getting two independent coefficient estimates ![]() is through data splitting. When estimating the linear model in equation (1), we can get

is through data splitting. When estimating the linear model in equation (1), we can get ![]() from one half of the data and

from one half of the data and ![]() from the other half of the data. While this is simple and intuitive it can result in loss of statistical power. To alleviate this concern, we can do repeated data splitting and aggregate the results in the end. This is reminiscent of the procedure suggested by Meinheusen et al. (2012) in the context of hypothesis testing in for high-dimensional regression. We can then determine the feature importance based on the share of data splits in which it ends up being included. I will omit the technical details here.

from the other half of the data. While this is simple and intuitive it can result in loss of statistical power. To alleviate this concern, we can do repeated data splitting and aggregate the results in the end. This is reminiscent of the procedure suggested by Meinheusen et al. (2012) in the context of hypothesis testing in for high-dimensional regression. We can then determine the feature importance based on the share of data splits in which it ends up being included. I will omit the technical details here.

There is a technical wrinkle I have omitted – the regression coefficients have to be standardized so that the ![]() s have comparable variances across variables. Check the original papers for details on exactly how to do that. Instead, I will now turn to the final algorithm for variable selection with FDR control using the approaches outlined above.

s have comparable variances across variables. Check the original papers for details on exactly how to do that. Instead, I will now turn to the final algorithm for variable selection with FDR control using the approaches outlined above.

Putting it All Together

This framework sets the stage for the following general algorithm for variable selection with FDR control:

- Calculate the

mirror statistics,

mirror statistics,  .

. - Given a FDR level

, set a threshold

, set a threshold  such that

such that

- Select the features

.

.

In words, given ![]() calculate the

calculate the ![]() ‘s, find the magical threshold

‘s, find the magical threshold ![]() and include the variables with

and include the variables with ![]() >

> ![]() .

.

Bottom Line

- The Benjamini-Hochberg approach is still the most popular way to control FDR.

- I discuss two novel approaches for variable selection and FDR control aimed at improving the knockoff filter.

Where to Learn More

This research is currently ongoing, so the best thing you can do is look at the papers in the section below.

References

Barber, R. F., & Candès, E. J. (2018). Controlling the false discovery rate via knockoffs. Annals of Statistics

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal statistical society: series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289-300.

Benjamini, Y., & Yekutieli, D. (2001). The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Annals of statistics, 1165-1188.

Dai, C., Lin, B., Xing, X., & Liu, J. S. (2022). False discovery rate control via data splitting. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 1-18.

Dai, C., Lin, B., Xing, X., & Liu, J. S. (2023). A scale-free approach for false discovery rate control in generalized linear models. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 1-15.

Ignatiadis, N., Klaus, B., Zaugg, J. B., & Huber, W. (2016). Data-driven hypothesis weighting increases detection power in genome-scale multiple testing. Nature methods, 13(7), 577-580.

Korthauer, K., Kimes, P. K., Duvallet, C., Reyes, A., Subramanian, A., Teng, M., … & Hicks, S. C. (2019). A practical guide to methods controlling false discoveries in computational biology. Genome biology, 20(1), 1-21.

Scott, J. G., Kelly, R. C., Smith, M. A., Zhou, P., & Kass, R. E. (2015). False discovery rate regression: an application to neural synchrony detection in primary visual cortex. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 110(510), 459-471.

Xing, X., Zhao, Z., & Liu, J. S. (2023). Controlling false discovery rate using gaussian mirrors. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 118(541), 222-241.

Leave a Reply