Background

Much of data science is concerned with learning about the relationships between different variables. The most basic tool to quantify relationship strength is the correlation coefficient. In 2021 Sourav Chatterjee of Stanford University published a paper outlining a novel correlation coefficient which has ignited many discussions in the statistics community.

In this article I will go over the basics of Chatterjee’s correlation measure. Before we get there, let’s first review some of the more traditional approaches in assessing bivariate relationship strength.

For simplicity, let’s assume away ties. Let’s also set hypothesis testing aside. All test statistics I describe below have well-established asymptotic theory for hypothesis testing and calculating p-values. Thus, we can gauge not only the strength of the relationship between the variables but also the uncertainty associated with that measurement and whether or not it is statistically significant.

Measuring Linear Relationships

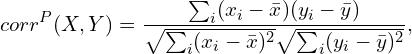

When we simply say “correlation” we refer to the so-called Pearson correlation coefficient. Virtually everyone working with data is familiar with it. Given a random sample ![]() of two random variables

of two random variables ![]() and

and ![]() it is computed by:

it is computed by:

where an upper bar denotes a sample mean.

This coefficient lives in the ![]() interval. Larger values indicate stronger relationship between

interval. Larger values indicate stronger relationship between ![]() and

and ![]() , be it positive or negative. At the extreme, the Pearson coefficient will equal 1 when all observations can be perfectly lined up on a upward sloping line. Yes, you guessed it – when it equals -1 the line is sloping down.

, be it positive or negative. At the extreme, the Pearson coefficient will equal 1 when all observations can be perfectly lined up on a upward sloping line. Yes, you guessed it – when it equals -1 the line is sloping down.

You can easily calculate the Pearson correlation in R:

cor(x,y, method = 'pearson')

cor.test(x,y, method = 'pearson', alternative='two.sided').This measure, while widely popular, suffers from a few shortcomings. First, outliers have an outsized impact in skewing its value. Sample means vulnerable to outliers are a key ingredient in the calculation, rendering the measure sensitive to data anomalies. Second, it is designed to detect only linear relationships. Two variables might have a strong but non-linear relationship which this measure will not detect. Lastly, it is not transformation-invariant, meaning that applying a monotone transformation to either of the variables will change the correlation value.

Let’s discuss some improvements to the Pearson correlation measure. Enter Spearman correlation.

Measuring Monotone Relationships

Spearman correlation is the Pearson correlation among the ranks of ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

![]()

where ![]() denotes an observation’s rank (or order) in the sample.

denotes an observation’s rank (or order) in the sample.

Spearman correlation is thus a rank correlation measure. As such, it quantifies how well the relationship between ![]() and

and ![]() can be described using a monotone (and not necessarily a linear) function. It is therefore a more flexible measure of association. Again, intuitively, Spearman correlation will take on a large positive value when the

can be described using a monotone (and not necessarily a linear) function. It is therefore a more flexible measure of association. Again, intuitively, Spearman correlation will take on a large positive value when the ![]() and

and ![]() observations have similar ranks. This value will be negative when the ranks tend to go in opposite directions.

observations have similar ranks. This value will be negative when the ranks tend to go in opposite directions.

Spearman correlation addresses some of the shortcomings associated with Pearson correlation. It is not easily influenced by outliers, and it does not change if we apply a monotone transformation of ![]() and/or

and/or ![]() . These benefits come at the expense of a loss in interpretation and potential issues when tied ranks are common, a scenario I ignore here.

. These benefits come at the expense of a loss in interpretation and potential issues when tied ranks are common, a scenario I ignore here.

Calculating it in R is just as simple:

cor(x,y, method = 'spearman')

cor.test(x,y, method = 'spearman', alternative='two.sided').Spearman correlation is not the only rank correlation coefficient out there. А popular alternative is the Kendall rank coefficient which is computed slightly differently. Let’s define a pair of observations ![]() and

and ![]() to be agreeing (the technical term is concordant) if the differences

to be agreeing (the technical term is concordant) if the differences ![]() and

and ![]() have the same sign (i.e., either both

have the same sign (i.e., either both ![]() and

and ![]() or both

or both ![]() and

and ![]() ).

).

Then, Kendall’s coefficient is expressed as:

![]()

So, it quantifies the degree of agreement between the ranks of ![]() and

and ![]() . Like the other coeffients described above, its range is [-1, 1] and values away from zero indicate stronger relationship.

. Like the other coeffients described above, its range is [-1, 1] and values away from zero indicate stronger relationship.

Again, this coefficient is similarly computed in R:

cor(x,y, method = 'kendall')

cor.test(x,y, method = 'kendall', alternative='two.sided').Kendall’s measure improves on some of the shortcomings baked in the Spearman’s coefficients – it has a clearer interpretation and it is less sensitive to rank ties.

However, none of these rank correlation coefficients can detect non-monotonic relationships. For instance, ![]() and

and ![]() can have a parabola- or wave-like pattern when plotted against each other. We would like a correlation measure flexible enough to capture such non-linear relationships.

can have a parabola- or wave-like pattern when plotted against each other. We would like a correlation measure flexible enough to capture such non-linear relationships.

This is where Chatterjee’s coefficient comes in.

Measuring More General Relationships

Chatterjee recently proposed a new correlation coefficient designed to detect non-monotonic relationships. He discovered a novel estimator of a population quantity first proposed by Dette et al. (2013).

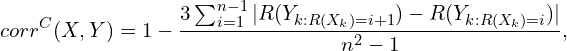

Let’s start with the formula. The Chatterjee correlation coefficient is calculated as follows:

where ![]() is the sample size. This looks complicated, so let’s try to simplify the numerator. Let’s sort the data in an ascending order of

is the sample size. This looks complicated, so let’s try to simplify the numerator. Let’s sort the data in an ascending order of ![]() so that we have

so that we have ![]() , where

, where ![]() . Also, denote

. Also, denote ![]() be the rank of

be the rank of ![]() . Then:

. Then:

![]()

So, this new coefficient is a scaled version of the sum of the absolute differences in the consecutive ranks of ![]() when ordered by

when ordered by ![]() . ˆIt is perhaps best to think about Chatterjee’s method as a measure of dependence and not strictly a correlation coefficient.

. ˆIt is perhaps best to think about Chatterjee’s method as a measure of dependence and not strictly a correlation coefficient.

There are some major difference comapred to the previous correlation measures. Chatterjee’s correlation coefficient lies in the [0,1] interval. It is equal to zero if and only if ![]() and

and ![]() are independent and to one if one of them is a function of the other. Unlike the coefficients descibed above, it is not symmetric in

are independent and to one if one of them is a function of the other. Unlike the coefficients descibed above, it is not symmetric in ![]() and

and ![]() , meaning

, meaning ![]() . This is understandable since we are interested in whether

. This is understandable since we are interested in whether ![]() is a function of

is a function of ![]() , which does not imply the opposite. The author also develops asymptotic theory for calculating p-values although some researchers have raised concerns about the coefficient’s power.

, which does not imply the opposite. The author also develops asymptotic theory for calculating p-values although some researchers have raised concerns about the coefficient’s power.

Here is a sample R code to calculate its value:

n <- 1000

x <- runif(n)

y <- 5 * sin(x) + rnorm(n)

data <- data.frame(x=x, y=y)

data$R <- rank(data$y)

data <- data[order(data$x), ]

1 - 3 * sum(abs(diff(data$R))) / (n^2-1)Alternatively, you can used the XICOR R package.

There you have it. You are now well-equipped to dive deeper into your datasets and find new exciting relationships.

Bottom Line

- There are numerous ways of measuring association between two variables.

- The most common methods measure only linear or monotonic relationships. These are often useful but do not capture more complex, non-linear associations.

- A new correlation measure, Chatterjee’s coeffient, is designed to go beyond monotonicty and assess more general bivariate relationships.

Where to Learn More

Wikipedia has detailed entries on correlation, rank correlation, and Kendall’s coefficient which I found helpful. The R bloggers platform has articles exploring the Chatterjee’s correlation coefficient in detail. The more technically oriented folks will find Chatterjee’s original paper helpful.

References

Chatterjee, S. (2021). A new coefficient of correlation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 116(536), 2009-2022.

Dette, H., Siburg, K. F., & Stoimenov, P. A. (2013). A Copula‐Based Non‐parametric Measure of Regression Dependence. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 40(1), 21-41.

Shi, H., Drton, M., & Han, F. (2022). On the power of Chatterjee’s rank correlation. Biometrika, 109(2), 317-333.

Leave a Reply