Background

Imagine you’re a data scientist evaluating an A/B test of a new recommendation algorithm. The results show a modest but promising 0.5% lift in conversion rate—up from 8% to 8.5% across 20,000 users—along with a p-value of 0.06. Given historical data, the improvement seems realistic, the cost to implement is low, and the projected revenue impact is substantial. Yet, the conventional analysis compels you to “fail to reject the null hypothesis” simply because the p-value doesn’t meet an arbitrary 0.05 threshold.

Traditional A/B testing approaches (randomized controlled trials or RCTs) rely primarily on frequentist methods like t-tests or chi-squared tests to detect differences between treatment and control groups. For more precision, analysts often adjust for covariates in linear models. After weeks or months of testing, however, these methods often boil down to a single outcome: the p-value. This binary interpretation—significant or not—can obscure valuable insights, as seen in the example above.

Bayesian statistics, by contrast, offers a more nuanced and potentially more informative alternative. In this article, we’ll walk through a practical example, discuss the implementation details, and dive into the Bayesian framework’s mathematical foundations for experimentation. One of the core advantages of the Bayesian approach is its ability to produce a full posterior distribution, offering a richer view of the experiment’s outcomes beyond just point estimates.

This article assumes a familiarity with Bayesian fundamentals like priors, posteriors, and conjugate distributions. If you’d like a refresher, see the References section below.

Notation

Let’s establish our notation for a binary intervention A/B test:

: Treatment indicator

: Treatment indicator : Number of units in treatment group

: Number of units in treatment group : Number of units in control group

: Number of units in control group : Total sample size

: Total sample size : Number of “successes” in treatment group

: Number of “successes” in treatment group : Number of “successes” in control group

: Number of “successes” in control group : Success rate (e.g., conversion rate, employment status).

: Success rate (e.g., conversion rate, employment status).

Diving Deeper

We are interested in making inferences about the treatment effect, ![]() , of the intervention

, of the intervention ![]() on the success rate

on the success rate ![]() . In Bayesian terms, this means we seek the posterior distribution of

. In Bayesian terms, this means we seek the posterior distribution of ![]() . Once we obtain this distribution or can draw observations from it, we can calculate various statistics to summarize the impact of the intervention, potentially providing a richer understanding of its effects.

. Once we obtain this distribution or can draw observations from it, we can calculate various statistics to summarize the impact of the intervention, potentially providing a richer understanding of its effects.

The Bayesian methodology of analyzing experiments proceeds in four steps.

Step 1: Specify the Prior Distribution

We begin by choosing the prior distributions for ![]() . The prior distribution represents our beliefs about the parameter before seeing the data. It is usually informed by previous A/B testing experience combined with deep context knowledge. For example, we might believe that the treatment effect is around two percentage points (

. The prior distribution represents our beliefs about the parameter before seeing the data. It is usually informed by previous A/B testing experience combined with deep context knowledge. For example, we might believe that the treatment effect is around two percentage points (![]() ) with some uncertainty around it.

) with some uncertainty around it.

Given our binary outcome, the Beta distribution serves as a natural conjugate prior:

![]()

Step 2: Specify the Likelihood Function

For binary outcomes, we model the data using a Binomial distribution:

![]()

This choice reflects the inherent structure of our data: counting successes in a fixed number of trials. We are now ready to use the Bayes rule to arrive at the posterior distributions.

Step 3: Posterior Distributions Derivation

Thanks to conjugacy between Beta and Binomial distributions, we obtain closed-form posterior distributions:

![]()

This mathematical convenience allows us to avoid more complex numerical methods like MCMC sampling. We can now even plot the two posterior distributions and visually asses their differences.

Step 4: Inference and Decision Making

The Bayesian framework enables rich analysis beyond traditional frequentist-style hypothesis testing. Here are some examples:

Example 1: Probability of Positive Impact

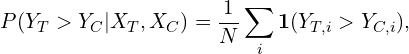

We can calculate the probability that the outcomes for the treatment group are higher than those of the control group. In closed form, we have:

where ![]() is the indicator function. This is simply share of observations for which

is the indicator function. This is simply share of observations for which ![]() .

.

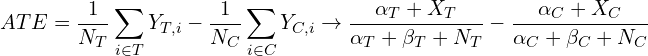

Example 2: Average Treatment Effect

Another potential example of an object of interest is the Average Treatment Effect (ATE):

![]()

And that’s it. You see how with the cost of additional assumptions we get much more than a single p-value, and that’s where much of the appeal of this approach lies.

Advantages

Overall, Bayesian thinking entails some compelling advantages:

- Incorporation of Prior Information. It allows you to incorporate prior knowledge or expert opinion into the analysis. This is particularly useful when historical data or domain expertise is available.

- Probabilistic Interpretation: It provides direct probabilistic interpretations of the results, such as the probability that one variant is better than another. This may be more intuitive than frequentist p-values, which are often misinterpreted.

- Handling of Small Sample Sizes: It tends to perform better with small sample sizes because they incorporate prior distributions, which can regularize estimates and prevent overfitting.

- Continuous Learning: As new data comes in, Bayesian methods provide a natural way to update the posterior distribution, leading to continuous learning and adaptation.

The downsides are mostly related to the choice of prior distribution. In settings where there is a lack of expert knowledge, this Bayesian approach to experimentation might not be very attractive. Computation can also be an issue in more complex settings.

An Example

Let’s code an example in R. We start with generating some fake data and selecting parameters for the prior distributions.

rm(list=ls())

set.seed(681)

library(ggplot2)

# Data: Number of successes and total observations for T and C

n_T <- 1000

x_T <- 70

n_C <- 900

x_C <- 50

# Prior parameters for the Beta distribution

alpha_A <- 1

beta_A <- 1

alpha_B <- 1

beta_B <- 1We are now ready to get to and sample from the posteriors.

# Posterior parameters

posterior_alpha_T <- alpha_T + x_T

posterior_beta_T <- beta_T + n_T - x_T

posterior_alpha_C <- alpha_C + x_C

posterior_beta_C <- beta_C + n_C - x_C

# Sample from the posterior distributions

posterior_obs_T <- rbeta(10000, posterior_alpha_T, posterior_beta_T)

posterior_obs_C <- rbeta(10000, posterior_alpha_C, posterior_beta_C)We are already at the final step, calculating the statistics of interest.

# Sample from the posterior distributions

posterior_obs_T <- rbeta(10000, posterior_alpha_T, posterior_beta_T)

posterior_obs_C <- rbeta(10000, posterior_alpha_C, posterior_beta_C)

# Estimate the probability that T is better than C

prob_T_better <- mean(posterior_obs_T > posterior_obs_C)

print(paste("Probability that T is better than C:", round(prob_T_better, digit=3)))

# Estimate the average treatment effect

treatment_effect <- mean(posterior_obs_T - posterior_obs_C)

print(paste("Average change in Y b/w T and C:", round(treatment_effect, digit=3)))

treatment_effect_limit <- (alpha_T + x_T)/(alpha_T + beta_T + n_T) - (alpha_C + x_C)/(alpha_C + beta_C + n_C)

print(treatment_effect_limit)Lastly, we can even plot both posteriors distributions.

df <- data.frame(

y = c(posterior_obs_T, posterior_obs_C),

group = factor(rep(c("T", "C"), each = 10000))

)

ggplot(df, aes(x = y, fill = group)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.5) +

labs(title = "Posterior Distributions of Outcomes",

x = "Y = 1", y = "Density") +

theme_minimal()

You can find the code in this GitHub repo. There is also a specalized bayesAB R package. It produces some cool charts, so I definitely recommend giving it a try.

Software Package: bayesAB

Bottom Line

- Bayesian inference offers a compelling alternative to the traditional methods based on frequentist statistics.

- The main idea rests on incorporating prior information on the success rates in the treatment and control group as a starting point.

- Advantages of bayesian methods include incorporating prior information, providing probabilistic interpretations, handling small sample sizes better, and enabling continuous learning.

- The main challenge is the choice of prior distribution, which can be difficult without expert knowledge.

Where to Learn More

Accessible introductions to the world of Bayesian inference are common. An example is Will Kurt’s book “Bayesian Statistics the Fun Way“. See also the papers I cite below. As almost everything else, Google is also a great starting point.

References

Deng, A. (2015, May). Objective bayesian two sample hypothesis testing for online controlled experiments. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web (pp. 923-928).

Kamalbasha, S., & Eugster, M. J. (2021). Bayesian A/B testing for business decisions. In Data Science–Analytics and Applications: Proceedings of the 3rd International Data Science Conference–iDSC2020 (pp. 50-57). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Kurt, Will. Bayesian statistics the fun way: understanding statistics and probability with Star Wars, Lego, and Rubber Ducks. No Starch Press, 2019.

Stevens, N. T., & Hagar, L. (2022). Comparative probability metrics: using posterior probabilities to account for practical equivalence in A/B tests. The American Statistician, 76(3), 224-237.

Leave a Reply