Background

Gradient boosting has emerged as one of the most powerful techniques for predictive modeling. In its simplest form, we can think of gradient boosting like having a team of detectives working in sequence, where each new detective specifically focuses on solving the cases where their predecessors stumbled. Each detective contributes their findings to the investigation, with earlier ones catching obvious clues and later ones piecing together the subtle evidence that was initially missed. The final solution emerges from combining all their work.

While the term “gradient boosting” is often used generically, there are notable differences among its implementations—each with unique strengths, weaknesses, and practical applications. Understanding these nuances is essential for advanced data scientists aiming to choose the best method for their specific datasets and computational constraints.

This article aims to provide a brief overview of the most popular gradient boosting methods, delving into their mathematical foundations and unique characteristics. By the end, you will have a clearer understanding of when and how to use each method to achieve the best results in your predictive modeling tasks. At the end of the article, I’ll provide a step-by-step Python example that implements these algorithms.

I assume a mathematical familiarity with machine learning (ML) basics and some minimal previous exposure to gradient boosting. If you need a refresher, grab any introductory ML textbook.

Notation

Before diving into the specifics of each method, let’s establish some common notation that will be used throughout this article:

: Covariates/features matrix

: Covariates/features matrix : Outcome/target variable

: Outcome/target variable : Predictive model

: Predictive model : Loss function

: Loss function : Predicted outcome/target value

: Predicted outcome/target value : Learning rate

: Learning rate : Number of observations/instances

: Number of observations/instances : Number of algorithm iterations

: Number of algorithm iterations

Diving Deeper

Refresher on Gradient Boosting

Gradient boosting is an ensemble machine learning technique that builds models sequentially, each new model attempting to correct the errors of the previous ones. The general idea is to minimize a loss function by adding weak learners (typically short decision trees) in a stage-wise manner to arrive at a single strong learner. This iterative process allows the model to improve its performance gradually, making it highly effective for complex datasets. Gradient boosting methods are versatile in that they can be used both for regression and classifications problems. In the most common case when the weak learners are decision trees, the algorithm is known as gradient tree boosting.

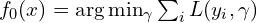

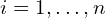

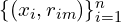

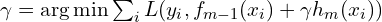

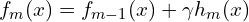

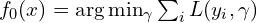

Mathematically, the model is built as follows:

- Initialize the model with a constant value:

- For

to

to  :

:

- Compute the pseudo-residuals:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com r_{im} = -\left[ \frac{\partial L(y_i, f(x_i))}{\partial f(x_i)} \right]_{f(x)=f_{m-1}(x)}](https://yasenov.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-72006c2982a29a4395ef6e7e12e325f2_l3.png) for

for  . In regression tasks this is simply

. In regression tasks this is simply  .

. - Fit a weak learner such as a tree,

, on

, on  .

. - Compute

by solving:

by solving:  .

. - Update the model:

.

.

- Compute the pseudo-residuals:

- The final model is

.

.

This is the most generic recipe for a gradient boosting algorithm. Let’s now focus on more specific implementations of this idea.

AdaBoost

AdaBoost, short for Adaptive Boosting, is one of the earliest boosting algorithms. It adjusts the weights of incorrectly classified observations so that subsequent learners focus more on difficult ones. In other words, it works by learning from its mistakes – after each round of predictions, it identifies which observartions it got wrong and pays special attention to them (i.e., gives them a higher weight) in the next round. Thus, AdaBoost is not strictly speaking a gradient boosting algorithm, in the modern sense of the term.

Let’s consider a binary classification problem where the outcome variable takes values in ![]() . Here is the general AdaBoost algorithm:

. Here is the general AdaBoost algorithm:

- Initialize weights

for

for  .

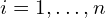

. - For

to

to :

:

- Train a weak learner

using weights

using weights  .

. - Compute the weighted error:

where

where  is the indicator function.

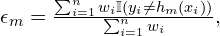

is the indicator function. - Compute the model weight:

.

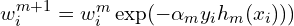

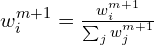

. - Update and normalize the weights:

, and

, and  for

for  .

.

- Train a weak learner

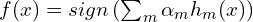

- The final model is

.

.

AdaBoost is simple to implement while being relatively resistant to overfitting, making it especially effective for problems with clean, well-structured data. Its adaptive nature means it can identify and focus on the most challenging observations. However, AdaBoost has notable weaknesses: it’s highly sensitive to noisy data and outliers (since it increases weights on misclassified examples), can perform poorly when working with insufficient training data, and tends to be computationally intensive compared to newer, simpler algorithms.

Software Packages. R: adabag, gbm. Python: scikit-learn.

XGBoost

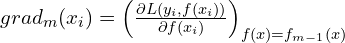

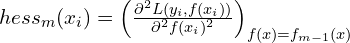

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) is an optimized implementation of gradient boosting designed for speed and performance. It revolutionizes the method by using the Newton-Raphson method in function space, setting it apart from traditional gradient boosting’s simpler gradient descent approach. At its core, XGBoost leverages both the first and second derivatives of the loss function through a second-order Taylor approximation. This sophisticated approach enables faster convergence and more accurate predictions by making better-informed decisions about how to improve the model at each step. When building decision trees, XGBoost considers both the expected improvement and the uncertainty of potential splits, while simultaneously applying regularization to prevent overfitting.

With some simplifications, the regression version of the XGBoost is implemented as follows:

- Initialize the model with a constant value:

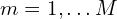

- For

:

:

- Compute the gradients

and hessians

and hessians  of the loss function for

of the loss function for  .

. - Fit a weak learner such as a tree,

on

on  .

. - Update the model

- Compute the gradients

- The final model is

.

.

XGBoost is ideal for large datasets and competitions where model performance is critical. It is also a good choice when you need a highly optimized and scalable solution as it is highly efficient, supports parallel and distributed computing. Nevertheless, this algorithm can be complex to tune, and may require significant computational resources for very large datasets.

Next up is CatBoost.

Software Packages: R: xgboost, Python: xgboost.

CatBoost

CatBoost, short for Categorical Boosting, is a gradient boosting library that handles categorical features efficiently. It uses ordered boosting to reduce overfitting and supports GPU training, making it both powerful and versatile. CatBoost modifies the standard gradient boosting algorithm by incorporating two novel techniques – ordered boosting and target statistics for categorical features. Let’s examine each one in turn.

Rather than requiring preprocessing like one-hot encoding, CatBoost encodes categorical values based on the distribution of the target variable without introducing data leakage. This is achieved by encoding each data point as if it were unseen, preventing overfitting. Additionally, ordered boosting is a method that builds each new tree while treating each data point as “out-of-fold” for itself. This helps reduce overfitting, particularly in small datasets, by preventing over-reliance on individual observations during training.

We now move on to a popular, faster gradient boosting implementation.

Software Packages: R: catboost, Python: catboost.

LightGBM

LightGBM shares many of XGBoost’s benefits, such as support for sparse data, parallel training, multiple loss functions, regularization, and early stopping, but it also introduces a bunc of new features and improvements.

First, rather than growing trees level-wise (row by row) as in most implementations, LightGBM grows trees leaf-wise, selecting the leaf that provides the greatest reduction in loss. Second, it does not use the typical sorted-based approach for finding split points, which sorts feature values to locate the best split. Instead, it relies on an efficient histogram-based method that significantly improves both speed and memory efficiency. Third, LightGBM incorporates the so-called Gradient-Based One-Side Sampling, which speeds up training by focusing on the most informative samples. Lastly, the algorithm uses Exclusive Feature Bundling which can group features to reduce dimensionality, enabling faster and more accurate model training.

Software Packages: R: lightgmb, Python: lightgbm.

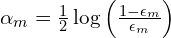

Challenges

Gradinet boosting methods comes with a few common practical challenges. When a predicitve model learns the training data too precisely, it may perform poorly on new, unseen data – a problem called overfitting. To combat this, various regularization methods are used to add helpful constraints to the learning process. A main parameter that regulates the model’s learning precision is the number of boosting rounds (![]() ), which determines how many base models are created. While using more rounds reduces training errors, it also increases overfitting risk. To find the optimal

), which determines how many base models are created. While using more rounds reduces training errors, it also increases overfitting risk. To find the optimal ![]() value, it’s common to use cross validation. The depth of decision trees is another important control parameter in tree boosting. Deeper trees can capture more complex patterns but are more prone to memorizing the training data rather than learning generalizable patterns.

value, it’s common to use cross validation. The depth of decision trees is another important control parameter in tree boosting. Deeper trees can capture more complex patterns but are more prone to memorizing the training data rather than learning generalizable patterns.

The improved predictive performance of gradient boosting relative to simpler models comes at a cost of reduced model transparency. While a single decision tree’s reasoning can be easily traced and understood, tracking the decision-making process across numerous trees becomes extremely complex and challenging. Gradient boosting is an excellent example of the inherent tradeoff between model simplicity and performance.

Let’s now look at how can we use these methods in practice.

An Example

I used GitHub copilot to create code illustrating the implementation of each algorithm described above on a common dataset. Let’s look at it in detail.

We start with loading the necessary libraries.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, cross_val_score

from sklearn.ensemble import AdaBoostClassifier

from xgboost import XGBClassifier

from lightgbm import LGBMClassifier

from catboost import CatBoostClassifier

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_scoreNext, we load the data and split it into training and test parts.

data = load_breast_cancer()

X = data.data

y = data.target

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)Now it’s time to define and implement the boosting algorithms. Do not forget to save the results.

classifiers = {

"AdaBoost": AdaBoostClassifier(n_estimators=100, random_state=42),

"XGBoost": XGBClassifier(n_estimators=100, use_label_encoder=False, eval_metric='logloss', random_state=42),

"LightGBM": LGBMClassifier(n_estimators=100, random_state=42),

"CatBoost": CatBoostClassifier(n_estimators=100, verbose=0, random_state=42)

}

results = {}

for name, clf in classifiers.items():

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = clf.predict(X_test)

accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)

results[name] = accuracyFinally, we print the accuracy results:

for name, accuracy in results.items():

print(f"{name}: {accuracy:.4f}")

AdaBoost: 0.9737

XGBoost: 0.9561

LightGBM: 0.9649

CatBoost: 0.9649Overall each method performed reasonably well, with acuracy ranging from 95.6% to 97.4%. Interestingly, Adaboost outperformed the other more complex algorithms, at least in the in terms of accuracy.

You can find the entire code in this GitHub repo.

And that’s it. You are now familiar with the most popular implementations of gradient boosting along with their advantages and weaknesses. You also know how to employ them in practice. Have fun incorporating XGboost and the like into your predictive modeling tasks.

Bottom Line

- Gradient boosting is a powerful ensemble technique for predictive modeling that comes in a variety of flavors.

- AdaBoost focuses on misclassified instances by adjusting weights.

- XGBoost introduces regularization and optimization for speed and performance.

- CatBoost efficiently handles categorical features and reduces overfitting.

- LightGBM enjoys many of XGBoost’s strenghts while introducing a few novelties including a different way of building the underlying weak learners.

- Common practical challenges when implementing gradient boosting include overfitting, decreased interpretability and computational costs.

Where to Learn More

Wikipedia is a great startint point, and it’s a resource I used extensively when preparing this article. “The Elements of Statistical Learning” by Hastie, Tibshirani, and Friedman is a comprehensive guide that covers the theoretical foundations of machine learning, including gradient boosting. It is the de facto bible for statistical ML. While this book is phenomenal, it can be challenging for less technical practitioners for which I recommend its lighther versions, “An Introduction to Statistical Learning” with R and Python code. All these books are available for free online. Lastly, if you want to dive even deeper into any of the algortihms descibe above, consider studying the papers in the References section below.

References

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 785-794).

- Dorogush, A. V., Ershov, V., & Gulin, A. (2018). CatBoost: gradient boosting with categorical features support. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.11363.

- Freund, Y., & Schapire, R. E. (1997). A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. Journal of computer and system sciences, 55(1), 119-139.

- Friedman, J. H. (2001). Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Annals of Statistics, 29(5), 1189-1232.

- Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. (2017). The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction.

- James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Taylor, J. (2023). An introduction to statistical learning: With applications in python. Springer Nature.

- James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Taylor, J. (2013). An introduction to statistical learning: With applications in R. Springer Nature.

- Ke, G., Meng, Q., Finley, T., Wang, T., Chen, W., Ma, W., … & Liu, T. Y. (2017). Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30.

- Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V., & Gulin, A. (2018). CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. Advances in neural information processing systems, 31.

Leave a Reply